DEEP expects to put its first habitat in the water in 2025. We’re calling the project ‘Vanguard’, and this article takes you step by step through the upcoming stages of its development.

But first – what is Vanguard? And why are we building it?

Putting theory into practice

Vanguard, as the name hints at, is an engineering prototype. In future, after extensive testing and user feedback, it may well evolve to be a product in its own right that divers can dive from. But its purpose right now is to put what we’ve designed to the test in a real-world setting.

Will everything work as planned first time? Any experienced engineer will tell you the answer to this question is rarely ‘yes’. So what will we need to iterate? We’re going to find out.

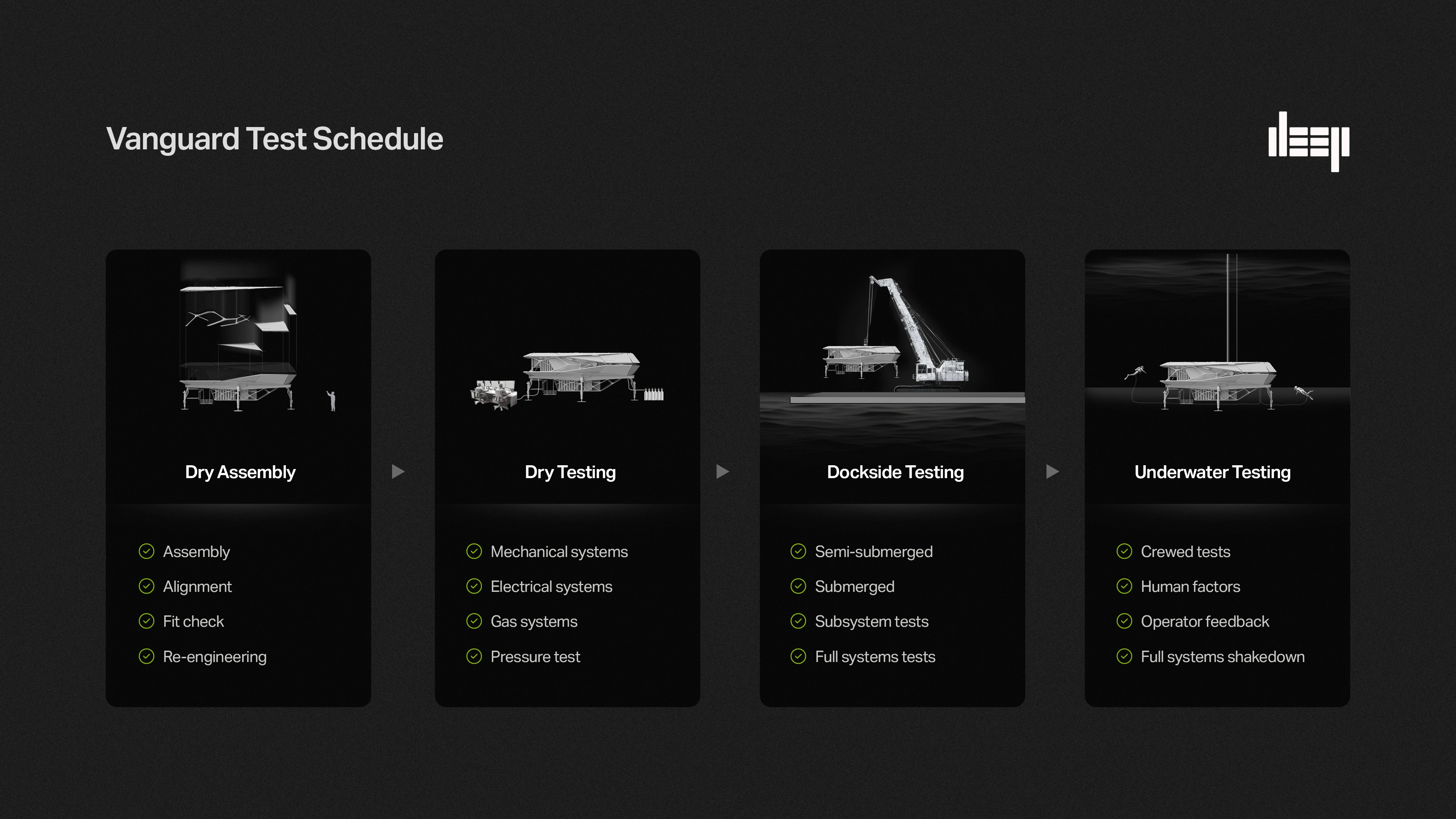

Dry assembly

The first step in building Vanguard is for all the individual parts, like the wet porch and the pressure vessel, to be fabricated and tested. This is happening now around the UK.

Once everything arrives at DEEP over the next couple of months, we move on to dry assembly. That means building the habitat on land. This is where we find out if everything fits together, if all the parts have been machined properly, and whether anything needs to be remade or redesigned.

No engineering organisation worth its salt relies on everything being exactly correct first time. That’s why dry assembly is essential.

Dry testing

Once we’ve assembled Vanguard and we’re happy with it, the next step is to test it on land.

For example, to dive from a habitat the gas pressure inside needs to match the water pressure outside, to prevent the sea coming in from the moon pool. So Vanguard will need to maintain that ambient pressure inside the vessel. This dry testing stage therefore includes pressurising the vessel with air to check for any leaks.

Dockside testing

When we’re satisfied that everything in Vanguard works on dry land, the next step is to put it in water. This starts with putting just the bottom part of the habitat in water beside a dock, so there’s easy access for testing and maintenance.

Here’s where we test for ground faults with the electrics, for example. This is an electromechanical assembly, going into water, so we want to make sure the electrical system is perfectly protected from the water outside.

From this point, it’s a case of lowering Vanguard deeper and deeper, still dockside, and continuing to test, until the water is up to its top hatch. At that point Vanguard will to all intents and purposes be submerged, but with access from the top for non-divers to run tests and carry out work on the habitat.

Underwater testing

The next phase is where we test Vanguard in the environment it’s intended to operate in. On the bottom, completely underwater, away from dockside support.

Air, power, drinking water, waste processing, and communications will be delivered from a structure on the surface, such as a buoy or a barge. This is where we’ll learn a lot about what Vanguard is like for divers to live in. The user feedback will give us ideas for any changes we could make to Vanguard itself, but will also be valuable information for designing the larger Sentinel system.

What will success mean?

Deploying and testing Vanguard will give us a lot of practical knowledge about designing, building, and operating an underwater human habitat.

Just as important though will be the message Vanguard sends out to the world. To our knowledge, there are currently no comparable habitats in active use or in development. The existence of a working habitat – and the user feedback to develop improved versions – will show what’s possible.

The goal is to achieve dramatic reductions in how long it takes divers to complete a mission at the bottom of the sea. Having divers stay at depth means they get much more working time down there, and only need to decompress at the end of the mission.

Our aim is to enable missions that currently take weeks to be done in just a few days. That makes them much more affordable, reducing for example the number of days support vessels need to be hired for.

It also considerably improves the odds of a mission’s success. A three-day weather forecast is a lot more reliable than a six-week one, so if you can do your mission in that timeframe, you can be much more confident it won’t have to be cancelled.

There are countless discoveries in the ocean waiting to be made. Success with Vanguard will open more of them up, and will be an important step towards making humans aquatic.

To see more, and to get updates on Vanguard’s progress in the weeks ahead, follow us on LinkedIn.